Wednesday 17 April 2013

Monday 15 April 2013

Friday 12 April 2013

Monday 8 April 2013

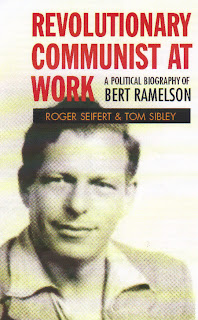

Revolutionary tale of an enemy within

.

Bert Ramelson's life was the stuff of legend. It needs neither embroidery nor embellishment.

He achieved the distinction of being personally denounced in the Commons by ministers in three different governments because he was such an effective national industrial organiser for the Communist Party.

Sinister figures in the business world, linked to intelligence and armed forces chiefs, feared the communist and broad left trade union apparatus that he did so much to help build and guide from the mid-1960s to the late 1970s.

Yet Ramelson had lived an extraordinary life even before that period. Born Baruch Rachmilevitch into a Yiddish-speaking community in Cherkassy, Ukraine, he was heavily influenced by the Bolsheviks in his own family, not least his big sister Rosa - later a "red professor" in economics and a prisoner in Stalin's labour camps.

While the Reds fought anti-semitism, the White Guards murdered some of his relatives in one of old Russia's frequent pogroms and his parents left for Canada. There Ramelson gained a law degree before spending the mid-1930s on a kibbutz in Palestine.

A Histadrut strike against the employment of Arab workers finished off his zionist sympathies. He returned home before travelling via London to enrol in the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion of the International Brigade in Spain, where he finally joined the illegal Canadian Communist Party.

Ramelson caught shrapnel and a bullet fighting Franco's fascists. While admiring the courage of many anarchist fighters, he also saw anarchist units withdrawing from the front line in order to support the Barcelona uprising against the Republican government. He witnessed the good-quality munitions supplied by the Soviet Union, later degraded by anti-Soviet propagandists who were not there.

Ramelson never forgot the lessons he learned in Spain - the need to make a concrete analysis of a concrete situation and to build broad unity in pursuit of immediate priorities.

He returned to Britain after two years, married his first wife Marian, who later wrote a ground-breaking class-based history of the struggle for women's rights, and set up home in Yorkshire.

During the second world war, which he believed became a people's anti-fascist war when the Churchill-Attlee coalition was formed, Ramelson served as a tank driver until his capture near Tobruk.

He was transported to Italy but escaped, met up with communist partisans, rejoined the British armed forces and ended up in India. There he played a leading role in the Forces Parliament which was soon closed down when it advocated Indian independence.

Back in Yorkshire after demobilisation, the Ramelsons fought against the right wing in the Usdaw union. Bert rose through the Communist Party ranks to become its district secretary. Together with Jock Kane, Frank Watters and Young Communist League and CP member Arthur Scargill he helped organise the historic turn to the left in the Yorkshire Area NUM.

Prime Minister Harold Wilson informed MPs from his MI5 reports that Ramelson had taken over from Peter Kerrigan as CP national industrial organiser by the beginning of 1966. Almost immediately, Ramelson was at the heart of the National Union of Seamen's strike that Wilson said was orchestrated by a "tightly knit group of politically motivated men."

Contrary to the impression given by his loud, rasping and accented voice, Ramelson was a persuader rather than an instructor. He respected the independence and democracy of trades unions.

The Communist strategy of mobilising rank-and-file workers to exert pressure on their leaders and make them more accountable was central to the advances made by the broad left and the Liaison Committee for the Defence of Trade Unions in the late 1960s and early '70s.

Biographers Roger Seifert and Tom Sibley rightly highlight the leading role played by Ramelson in helping to win the national miners' strikes of 1972 and 1974, spring the dockers' leaders from Pentonville jail and render the Industrial Relations Act inoperable. These battles vindicated his insistence on the transformative effects of intelligent struggle.

The authors also face head-on the charge from sections of the far left that he and the Communist Party betrayed Des Warren, who was framed and jailed for his part in picketing during the 1972 building workers' strike. Tactical differences did not prevent Ramelson and the party from doing everything possible to win Warren's freedom, as the latter had acknowledged before his capture by the Workers Revolutionary Party.

Those of us who met Warren saw for themselves the baleful impact of prison on every aspect of his health, and it is to Ramelson's credit that he and the party did not retaliate against the bitter words ascribed to Warren at the time.

Following Labour's return to office in 1974 Ramelson worked tirelessly to help turn the labour movement back towards free collective bargaining and the wages struggle after left-wing union leaders Jack Jones and Hugh Scanlon had signed the "social contract."

Ramelson argued from the outset - notably in Social Contract or Social Con-Trick, one of the biggest-selling political pamphlets in decades - that the unions were disarming themselves industrially and ideologically in pursuit of an illusory compromise with monopoly capital.

In one sense it was a pyrrhic victory, because the damage done by the Social Contract to left and labour movement unity had already sown the seeds of Thatcher's victory in 1979.

Ramelson handed the industrial organiser's baton to Mick Costello in 1977, focusing on international work and membership of the editorial board of the World Marxist Review in Prague.

It was a bold move. Following the Prague Spring, Ramelson had been summoned to the Soviet embassy in London on August 21 1968, when CP general secretary John Gollan was on holiday. When the Soviet ambassador sought to justify Warsaw Pact military intervention against the popular Czech communist government of Alexander Dubcek he met a blistering riposte from Ramelson.

This was not Hungary in 1956. There was no danger of fascist revanchism and he didn't believe a word about right-wing military plots by Dubcek's allies.

It was another milestone in Ramelson's journey of disenchantment with the Soviet Union. Towards the end of his life he came to believe that the Soviet party had abandoned its socialist objectives as early as the mid-1920s. His participation in the British party's 1956 investigation into Soviet anti-semitism had also shaken his faith more than he let on, compelling him to question his support for assimilation.

Yet his commitment to the essential work of a communist party in Britain remained undimmed. He urged workers to join it and trade unionists already inside to be active in their local party branch. At the same time, he emphasised the need for the Communist Party to work for broad left unity across the labour movement, especially in order to exert influence within and upon the Labour Party, for instance in favour of the Alternative Economic Strategy.

The authors recount Ramelson's own vigorous participation in major inner-party debates, not least around its programme The British Road to Socialism. The purges carried out by the revisionist party leadership in the 1980s led him to ponder whether "democratic centralism" could ever be implemented without a seemingly inevitable degeneration into bureaucratic centralism.

This may have been one of the reasons why, after opposing the liquidation of one section of the CP in 1991, he did not join the re-established Communist Party of Britain. Yet he agreed with much of its political outlook and remained a solid supporter of the Morning Star until his death in 1994.

Seifert and Sibley's tale of this titanic figure is a pleasure in more than one way - it also marks the welcome return of publishers Lawrence & Wishart to the service of the labour movement.

Its only notable shortcoming is that more use could have been made of CP archives to elaborate Ramelson's views while a member of the party's executive and political committees.

They have delivered a worthy biography of a magnificent life, recounting Ramelson's tale with precision, depth and insight.

Every thinking communist, socialist and militant trade unionist in Britain will benefit from reading it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Bob+&+wife+Doris.jpg)